3rd February 1764

Antoine Louis de Bougainville and his sixty plus settlers landed in the Falklands. They founded the first settlement and named it Fort Saint Louis. This was the beginning of the French period. Amongst this party was a Benedictine monk, Dom Antoine Pernetty. He also acted as botanist and chronicler, and records the first encounters with the warrahs’ aggression. ‘officers of M de Bougainville’s suite were attacked by a sort of wild dog; this is perhaps, the only savage animal and quadruped which exists on the Malouin’ he recorded,

and considered that ‘perhaps too, this animal is not actually fierce, and only came to present itself and approach us, because it had never seen men.’

It is interesting that Pernetty saw the warrah only as a sort of wild dog, not a wolf or fox, in any case coming from Europe the settlers would have taken no chances, bites could fester and even rabies might have came to mind, so the warrahs would not have been tolerated to live, or to interbreed with the settler’s dogs.

1767

John Byron mentions that four individuals were seen together, suggesting a social, organised pack animal, and that his people having suffered being ran directly at by these ‘creatures of great fierceness’, and after killing five of them, had set fire to the grass to get rid of them, so that the country was in a blaze as far as the eye could reach. The fire burned for several days and he reports that ‘we could see them running in great numbers to seek other quarters’. If the ‘grass’ was a white grass fire it would indeed look spectacular for as far as the eye could see, and if it was the tussac grass that was lit it may have burned down into the peaty soil to destroy a habitat forever. At any rate warrahs seem to have been quite comfortable and successful at this stage.

1836/37 Poor Pilot, the story of an Admiral, his Dog, and their encounters with the West Falklands Warrahs.

During the high summer months of 1836/ 37, when the weather is at its Falklands best, Admiral Hon. George Grey, (son of Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, after which the famous ‘Earl Grey Tea’ is named) set out to completely circumnavigate the Falklands. He was accompanied on the ship ‘HMS Cleopatra’ by his faithful dog ‘Pilot’.

Having navigated their way around the West, -the old English stronghold on Saunders ‘Port Egmont’ was visited, Pebble, and on to New Island where wild swans (could it be the rare black-necked) were shot ‘the first we had seen’. Penguin eggs were eaten by the sealers but declined by Admiral Grey, and he did take to task and punish some of his ship’s company for killing penguins with sticks. Passing the Arch Islands the Admiral not adverse to a little sport, ‘could not resist’ trying shoot a seal lion when they were spotted on a sandy beach, and remarked that it was such fun to see them floundering away into the water and making such a noise. Eventually a female cut off in the tussac, was set upon and after much confusion, and with the sailors and the beast both in great fright she was ‘cowardly murdered, my bore having helped’. ‘I have never laughed so much in my life’ recorded the Admiral. As the boat pushed off from the Arch Islands they managed to wound another lion.

January 1837 found the party at Port Edgar, West Falklands, probably in a warrah stronghold, as we know they favoured estuaries and coasts, and as this is close to ‘Fox Bay’ around the ‘waist’ of the West, where they would never have been too far from a coast and there were seal rookeries to scavenge easy pickings.

Pilot had probably disembarked before his master as the Admiral states ‘I had hardly put my foot on shore when one of the foxes of the country was chased by Pilot.’ Pilot was either incredibly brave or foolish, which ever view is taken. At any rate he seems to have been headstrong and outwith the Admiral’s control.

The Admiral had to run ‘to the poor dog’s assistance’ as having caught the warrah they had fell to fighting. Pilot had nearly met his match and the warrah was acquitting himself well, but a timely rifle ball ‘settled the business’ and aided by his master Pilot emerged the victor, but he had received a terrible bite in the leg. This was a very old warrah, wrote Admiral Grey ‘and I never saw such teeth’.

Having survived this injury, Pilot quickly forgot the encounter, where but for his faithful owner he may well have lost the fight. His leg hardly healed he returned the favour by loyally protecting the Admiral in a second incident involving a warrah attack.

Still presumably in the Port Edgar area, the Admiral had waded ashore, Pilot swimming behind him, and being cold ran up a slope, at the summit pausing to catch his breath and examine the country. Two ‘immense’ foxes came running up to him as if they would attack. Open mouthed, barking, howling, showing their teeth, and resembling wolves the warrahs greatly alarmed the Admiral who had at the time an unloaded rifle. Pilot, however bravely placed himself between him and the irate warrahs, keeping them at bay until Admiral Grey quickly loaded and was able to shoot the nearest one. Although this was a close shot, within six feet, the shot missed and only broke the warrah’s shoulder, but immediately the warrah was hit Pilot seized him and they fell to worrying and fighting, the other running off a short distance at the report of the shot but quickly returning to the aid of its mate. The Admiral meantime had reloaded and this time took better aim, the muzzle against the forehead of the warrah to ‘settle his business completely’, he then turned to old Pilot’s assistance, who alone, was getting the better of his badly wounded adversary. A blow on the warrah’s head with his gun butt ended the fight, and then Dowdle arrived to find Pilot and the Admiral ‘victorious’ and with a knife put the wounded warrah out of its misery.

Dowdle said that he had seen a cub running away and so the warrahs were in fact bravely defending a family, that the first came back to the aid of the second shows a good strong family structure, where even in a terrifying situation against aliens they could never encountered before they were prepared to fight to the death.

Pilot meantime, poor dog, had escaped very well, his old leg wound having not been touched, but had suffered a second bite to his hind leg, the blood spurting so far that it was feared an artery had been divided. The Admiral bound this with his own pocket handkerchief, ‘the poor beast licked my hand and appeared so grateful, this little event quite warmed me’ he wrote.

Having called on ‘Roberts’ to preserve the deceased warrah skins (a mat for the boat, and a very handsome one too) the Admiral pondered later that lying dead they did not look nearly as large as when they attacked him.

1840

Discontented with their treatment on board the American brigantine ‘Enterprize’, mastered by John Green, three sailors, namely Henry Whiteman (18 years, born in Great Britain but seems to have USA connections), Samuel Profit (24 years, of New Providence, USA) and John Bray landed with the brigantine’s dinghy in Queen Charlotte’s Sound in the north of West Falklands. Around two and a half months after their landing, and after various disagreements amongst themselves John Bray went his own way and we do not know what became of him, but Henry Whiteman and Samuel Profit survived to be picked up by Her Majesty’s ketch ‘Sparrow’ captained by John Tyssen in White Rock Harbour fourteen months later. The medical officer on board the ‘Sparrow’ reported them to be in perfect health, despite being exposed to an unusually severe winter.

He reported to HE Richard C Moody, the then Lieutenant-Governer of the islands.

They stated that they had survived on wildfowl, seals, tussac root and heather berries (could only have been diddle-dee,). All food was eaten raw apart from on two days due to their inability to easily produce fire. They did not experience severe weather, at least compared with that of the USA anyway. The berries would have been seasonal but the tussac root would be available even in winter. Given that they stated that tussac root was eaten every day we must assume that they followed the coast where the tussac which only flourishes by the sea would grow, and made their way up the western coast from Queen Charlotte Bay then along the northern to end up at White Rock. The tussac bogs can be very high like a forest and would have also given them shelter in any wind direction. This would also have certainly brought them into contact or conflict with warrahs. They may have even had to follow up the ‘Warrah River’ surely named for the fox, in what is now Port Howard camp, and whose mouth opens on to the north coast in order to find a place to ford it. Whiteman and Profit reported that at times they were attacked by the warrahs or foxes and had killed twelve of them. So at this point there still seemed to be plenty of them on West Falklands.

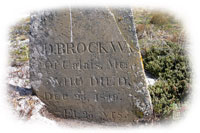

Brock and the warrah at 'Gun Hill' 1849

And  then there is the story or legend of the sailor ‘Brock’ who, on December 25 1849 was ashore near what is now called ‘Gun Hill’ on the shore of King George Bay, West Falkland. It is said that he died when he was digging a ‘fox’ out of its burrow with the stock of his gun when it went off and fatally wounded him………….. then there is the story or legend of the sailor ‘Brock’ who, on December 25 1849 was ashore near what is now called ‘Gun Hill’ on the shore of King George Bay, West Falkland. It is said that he died when he was digging a ‘fox’ out of its burrow with the stock of his gun when it went off and fatally wounded him…………..

If this is true then it must be the only time a warrah bettered a man.

James Lovegrove Waldron, writing up his notebook in 1866-67 says that ‘The Falkland Island Fox is inquisitive and if any one stands still, will fearlessly approach a man and even come to smell him, as I have witnessed.’

Photographic credits: Hurst, courtesy of Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm. Adult dog Warrah collected by J Frank 1847.

Sources and help: Dom. Pernety 1763-64. Historic d'un voyage aux Iles Maloaines. Renshaw, G. 1931, Mivart (1890) Mon. of Canidae, Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm, Sweden, Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles of Belgique, Brussels, Belgium. The World Museum, Liverpool. Voyage around the world by Louis de Bougainville 1766-9,Voyage of the Beage Charles Darwin, Falkland Heritage- Mary Trehearne. |

Warrah fur courtesy of Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm. Adult dog Warrah collected by J Frank 1847.

Warrah fur courtesy of Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm. Adult dog Warrah collected by J Frank 1847.